| INDEX | 1300-1599 | 1600s | 1700s | 1800s | 1900s | CROSS-ERA | ETHNO | |

| MISCELLANY | CONTACT | SEARCH | |

|

|

|

|

Woolen suit with gold trim, c. 1750 |

Suits were usually made of wool or silk, depending on the occasion and what the customer could afford. I only know one specimen made of linen in the museum in Ludwigsburg, and that's a strange one. As long as no other examples crop up, we should treat linen as a curiosity.

Wool is suitable for the lower classes, everyday suits of the middling sort, and travel, riding and hunting suits of the upper class right up to royalty. However, there are also extant suits that were so decorated with gold or silver braid that they were quite suitable for festive occasions (pic to the right). Silks were worn by the middling sort for festive occasions, and for everyday use by the upper class. Silk came in various qualities, from relatively simple taffeta, failles and satin via damask, corduroy, velvet up to lampas, brocade and silver-shot fabric. The higher the socio-economic status, the more likely it is to expect embroidery, sometimes even on multicoloured fabric where the embroidery didn't really stand out. The rule that money doesn't necessarily come with taste apparently appied back then, too.

Silk fabrics were often made especially for suit use and, from about 1720 on, even woven in such a way that the pattern conformed to the cut of a coat or waistcoat. Due to the purpose, the were relatively stiff if compared to modern silk fabrics*. Faille and duchesse satin are suitable, maybe heavy taffeta and, if you have the means, brocades and lampas from one of the few remaining manufactories in Lyon and Venice. The lighter silks require a stiff interfacing. It may seem sensible use modern iron-on interfacing, but unfortunately that is too conspicuous even from the outside, even to the untrained eye. So hands off iron-on interfacing! Use stiff linen or even horsehair interfacing instead. See also 18th century fabrics.

With suitable silks being on the expensive side, wool is an attractive alternative. The most suitable sort of wool fabric is linen weave with a felted, dull surface, i.e. the kind used for coats, only not as thick. Steer clear of the the densely woven and smooth kind (e.g. gabardine) used for most modern suits. Actually, twill weaves are not a good choice for pre-1760s suits because they are very bias-elastic. The rounded hem of the coat would distort like hell. Even for a later suit, a loosely woven twill is not really suitable. The suitable kind is low-maintenance: If it's been prewashed, you don't have to fear shrinking, it can be ironed at full heat, and it is somewhat water- and even dirt-repellent. As an added benefit, you can have two suits at once: With a waistcoat of the same fabric, it's a day suit for the middle-class burgher or nobleman; with a silk waistcoat, it's suitable for more formal occasions.

|

|

Fabric for a waistcoat |

During the first half of the century, coat, waistcoat and breeches were usually made of the same fabric. In the second half, the wiastcoat tended to be of a lighter colour, the coat and breeches of a darker one. Waistcoats of the first half of the century tended to have sleeves; during the latter half, sleeves were very rare. Only the front of the waistcoat was visible, so that normally the back of the waistcoat would be made of plain linen. If you look at very late (1790s/1800s) waistcoats, you will often notice that the top fabric only goes up to a line from neck to lower end of armscye, with plain linen above. This is further evidence that the coat was not taken off in public. In case of the longer, early-century waistcoats, the back flaps would also be covered with top fabric. Some waistcoats had the backs and sleeves made of the same silk as the front, but those were definitely upper class, as evidenced by the quality of the fabric and embroidery.

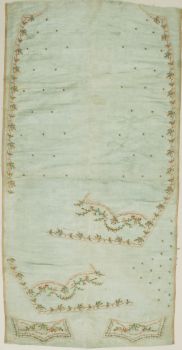

Class distinction mainly showed in the quality of the fabric, colours and trim (or absence thereof), which could consist e.g. of gold and silver borders or gold, silver and silk embroidery. By the way, embroidery also followed the lines of the cut: It was applied to the un-cut fabric along the future cut lines, sold that way and then taken to the tailor (see pic to the right - see how the embroidery follows the neck, front and hem line?). Therefore, modern embroidered fabrics aren't suitable, not just because the embroidery is conspicuously machine-made, but also because it does not follow the lines of the cut. If you can't afford hand-made bespoke embroidery, it's better to forgo it altogether. Suitable gold or silver borders are cheaper, but still hard to find and quite expensive. I've once tried to estimate the amount of trim needed for a suit and ended up somewhere in the vicinity of 12-15 metres. The one source I know for such borders asks 7€/m for something about as wide as on the blue suit above. Not quite as costly, but quite precious are fabric-covered buttons with gold/silver embroidery and embroidered buttonholes. There's an extra page on covering buttons.

In most cases, all three parts of the suit were made of the same fabric. In many other cases, coat and breeches were made of the same fabric, while the waistcoat could be made be made of a different, usually contrasing, fabric. Other combinations are rare and probably due to the fact that the breeches were the first to wear through while the rest of the suit was still good. The rich would, of course, discard the whole suit in such a case.

A commoner would usually wear an undecorated woolen suit in muted colours with a waistcoat of the same fabric. The only decoration were pewter buttons polished to a silver-like shine or invalidated silver coins with a loop soldered to the backside. Physical workers would, in an everyday setting, wear a sleeved waistcoat rather than the full suit.

The lining of coats was made of silk for the wealthy, linen-cotton mix for the less wealthy, or linen for anyone from poor to rich. It makes sense to line silk suits with silk and woolen ones with cotton or linen. Because silk was expensive, the back of the coat, which wasn't visible while the garment was worn, was often lined with a cheaper fabric in back, from shoulders to waist. My books don't tell which kind of silk was used. Taffeta wouldn't be wrong, and I think I remember mentions of coarse, slubby, low-grade silks such as Honan and Shandong. In any case, it helps if the lining has some stand. Linen is a good choice, both to lend stiffness and because of its cooling qualities. Its major drawback is the weight. My model coat, made of wool with partial linen interfacing and linen lining, weighs 2.3 kg. The guinea pig assures me that it's not too heavy.

The books don't mention the colour of the lining, either. Most extant suits I've seen so far had white or cream lining. Two red suits had red, and one** had pale blue lining. Meanwhile I have found some more coloured linings, but almost always in (a) late and (b) silk suits with silk lining, and in an estimated 10% of extant suits (which, in turn, tend to be upper-class silk suits). So coloured lining was the exception rather than the norm. Lining that matched the colour of the top fabric even more so. The contrast between cream lining and darker top fabric was not regarded as problematic, even though the lining often went all the way to the edges so that it was quite visible. In case of breeches and waistcoats, linen and cotton-linen-mix were the predominant lining. Breeches usually had lining only in the waistband. For the waistcoat, it makes sense to practically make it of linen and mount the top fabric onto the fronts. In case of the earlier, longer waistcoats, the lower back was also covered with top fabric.

So, how much fabric do we need?

The reckoning for the top fabric of a 1730s-1750s suit and 150 cm wide Fabric goes like this:

For the lining:

This usually amounts to about 6-7 metres of top fabric. For mock-ups, have the same amount of cheap fabric ready.

In addition, you need stiffening interlining, e.g. firm linen or horsehair. Silks need at least a layer of medium weight cotton all over. Independent of the stiffness of the top fabric, coat and waistcoat need a strip of interlining along the front edge and smaller pieces here and there. If the skirts are supposed to stick out as was common around 1730-40, they need full interlining.

A dressmaker's dummy is never amiss, but a helper with some sewing know-how and lots of patience is even better. BTW, I'm assuming that the future wearer is also the tailor. In the 21st century, men can tailor again without being badmouthed as cissy. Again, because up until the 17th century, tailoring was considered a male profession.

16 mdeium and 2 small buttons for the breeches (2 x 5 for the knee slit, 6 for the frint slit, 2 small ones for the pockets), 24 medium buttons for the waistcoat (18 front, 6 pockets), 32 large buttons for the justaucorps (16 front, 8 sleeve, 6 pockets, 2 skirt slits) plus at least two of each size for repairs. Choose flat or slightly curved buttons with a shaft, never ones with holes. Preferably brass, pewter, silver, gilded if you (that is, your persona) can afford it. If you find it easier to spend time than to spend money, consider fabric-covered buttons. You can hardly go wrong with them, and if you embroider them with silk floss, gold/silver thread and/or spangles, they may make an otherwise plain suit quite spectacluar. However, do not use store-bought moulds! Make them by hand. Another possibility are death-head buttons. I'm afraid you'll have to google for instructions for those.

Buttonhole silk (real silk, of couse) for the buttonholes. The amount depends on the style of the coat: Early ones may consume upwards of 70 metres; this 1750s coat probably consumed 40 metres. Later styles need less. For the chest padding, a good two handfuls preferably of unspun wool, but if you can't get that, cotton wool for cosmetic purposes will also work. No doll maker's poly wadding if you can help it!

A proper suit should also have knee buckles. Some of the sutlers on my purveyors page have replicas. An then, of course, you need the usual suspects: Needles, scissors, thread... For woolens, linen thread is the most suitable kind, even if it's undyed: That's perfectly authentic. If you're going to machine the seams, however, choose thread in the colour of the top fabric: When the seam is pulled apart under strain, the thread will show and betray your unauthentic technique. Fie! For silk fabrics, choose silk thread in the colour ot the top fabric.

The most important preparation is to decide which era you want to portray. Have a look at the guided tour through men's fashion and note how the cuffs, sleeve length, front edge, skirt size, collars etc. changed in time. Look at other pictures of the era you like best, e.g. by using the picture database. Never try to combine features of an earlier period with those of a later one, no matter how much you'd like to. The outcome can only be a chimera that may even look nice – but it won't be period.

If 1740-60 is your preferred period, you can use the pattern here. You can even stretch it up to 1765 for a conservative persona. With a different pattern and a grain of salt, the instructions here are good for anything from about 1720 until 1780. A bit earlier or later, the grain would become a pebble.

It is not absolutely necessary to pre-wash the fabric, but it makes sense to pre-wash wool at 40°C: If you've done that once before cutting, it can be done again, and fair fabrics may need it once in a while. At least the breeches. In case of silk, I'd rather advise against pre-washing as it would remove what little (compared to period silk) stiffness the fabric has.

Next chapter: The pattern

*) Waugh: The

Cut of Men's Clothes.

**) Baumgarten: Costume

Close Up

Wednesday, 15-May-2013 23:53:14 CEST

Content, layout and images of this page

and any sub-page of the domains marquise.de, contouche.de, lumieres.de, manteau.de and costumebase.org are copyright (c) 1997-2022 by Alexa Bender. All rights reserved. See Copyright Page. GDPO

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.